SMS Karlsruhe (1916)

SMS Karlsruhe en route to Scapa Flow 1919

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Karlsruhe |

| Namesake | Karlsruhe |

| Ordered | 1913 |

| Builder | Kaiserliche Werft Wilhelmshaven |

| Laid down | May 1915 |

| Launched | 31 January 1916 |

| Commissioned | December 1916 |

| Fate | Scuttled at Scapa Flow, 21 June 1919 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Königsberg-class light cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 151.4 m (496 ft 9 in) |

| Beam | 14.2 m (46 ft 7 in) |

| Draft | 5.96 m (19 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) |

| Range | 4,850 nmi (8,980 km; 5,580 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Crew |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Karlsruhe was a light cruiser of the Königsberg class, built for the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) during World War I. She was named after the earlier Karlsruhe, which had sunk in November 1914, from an accidental explosion. The new cruiser was laid down in 1914 at the Kaiserliche Werft shipyard in Kiel, launched in January 1916, and commissioned into the High Seas Fleet in November 1916. Armed with eight 15 cm SK L/45 guns, the ship had a top speed of 27.5 kn (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph).

She saw relatively limited service during the war, due to her commissioning late in the conflict. She was present during a brief engagement with British light forces in August 1917, though she did not actively participate in the battle. She joined the large task force assigned to Operation Albion in October 1917, but did not see significant action during that operation either. She was assigned to what was to have been the final sortie of the High Seas Fleet in the closing days of the war, but a large-scale mutiny in significant parts of the fleet forced the cancellation of the plan. Karlsruhe was interned in Scapa Flow after the end of the war, and scuttled there on 21 June 1919. Unlike most of the other ships sunk there, her wreck was never raised.

Design

[edit]Design work began on the Königsberg-class cruisers before construction had begun on their predecessors of the Wiesbaden class. The new ships were broadly similar to the earlier cruisers, with only minor alterations in the arrangement of some components, including the forward broadside guns, which were raised a level to reduce their tendency to be washed out in heavy seas. They were also fitted with larger conning towers.[1]

Karlsruhe was 151.4 meters (496 ft 9 in) long overall and had a beam of 14.2 m (46 ft 7 in) and a draft of 5.96 m (19 ft 7 in) forward. She displaced 5,440 t (5,350 long tons) normally and up to 7,125 t (7,012 long tons) at full load. The ship had a fairly small superstructure that consisted primarily of a conning tower forward. She was fitted with a pair of pole masts, the fore just aft of the conning tower and the mainmast further aft. Her hull had a long forecastle that extended for the first third of the ship, stepping down to main deck level just aft of the conning tower, before reducing a deck further at the mainmast for a short quarterdeck. The ship had a crew of 17 officers and 458 enlisted men.[2]

Her propulsion system consisted of two sets of steam turbines that drove a pair of screw propellers. Steam was provided by ten coal-fired and two oil-fired Marine-type water-tube boilers that were vented through three funnels. The engines were rated to produce 31,000 shaft horsepower (23,000 kW), which provided a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). At a more economical cruising speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph), the ship had a range of 4,850 nautical miles (8,980 km; 5,580 mi).[2]

The ship was armed with a main battery of eight 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, four were located amidships, two on either side, and two were arranged in a superfiring pair aft.[3] They were supplied with 1,040 rounds of ammunition, for 130 shells per gun. Karlsruhe also carried two 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 anti-aircraft guns mounted on the centerline astern of the funnels. She was also equipped with a pair of 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes with eight torpedoes in deck-mounted swivel launchers amidships. She also carried 200 mines.[2]

The ship was protected by a waterline armor belt that was 60 mm (2.4 in) thick amidships. Protection for the ship's internals was reinforced with a curved armor deck that was 60 mm thick; the deck sloped downward at the sides and connected to the bottom edge of the belt armor. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides.[2]

Service history

[edit]Karlsruhe was ordered under the contract name "Ersatz Niobe" and was laid down at the Kaiserliche Werft shipyard in Kiel on 5 May 1915.[4] She was launched on 31 January 1916 without ceremony due to the war, after which fitting-out work commenced. She was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet on 15 November 1916. She was not allocated to a fleet unit until 22 February 1917, when she was assigned to II Scouting Group. She thereafter served with the other cruisers of the unit in conducting defensive patrols in the German Bight to guard against British incursions. She also supported minelaying and minesweeping operations, the first of which took place on 5 March. Karlsruhe escorted a group of minesweepers into the German Bight to clear a British minefield. Another operation took place on 6 April; Karlsruhe, the light cruiser Graudenz, and the 2nd Torpedo-boat Half-Flotilla sortied to the Amrun Bank to rescue the submarine U-22, which had been damaged and needed assistance returning to port.[5]

On 16 August 1917, Karlsruhe participated in a mine-sweeping operation in the North Sea. The minesweepers were clearing Route Yellow, one of the channels in the minefields used by U-boats to leave and return to port. Karlsruhe was joined by the cruiser SMS Frankfurt and three torpedo boats. At 12:55, lookouts on one of the minesweepers spotted a British squadron of three light cruisers and sixteen destroyers approaching. The minesweepers fled south under cover of smoke screens, after which the British broke off the attack. Karlsruhe and the rest of the escort failed to come to their aid, however, and the commander of the operation was subsequently relieved of command.[6]

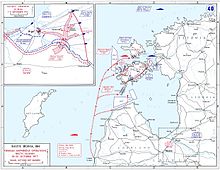

Operation Albion

[edit]

In early September 1917, following the German conquest of the Russian port of Riga, the German navy decided to eliminate the Russian naval forces that still held the Gulf of Riga. Karlsruhe took part in training exercises that month with the rest of II Scouting Group in preparation for the attack. The Admiralstab (Navy High Command) planned Operation Albion to seize the Baltic island of Ösel, and specifically the Russian gun batteries on the Sworbe Peninsula. On 18 September, the order was issued for a joint operation with the army to capture Ösel and Moon Islands; the primary naval component comprised the flagship, the battlecruiser Moltke, along with the III and IV Battle Squadrons of the High Seas Fleet. The invasion force amounted to approximately 24,600 officers and enlisted men.[7] Karlsruhe and the rest of II Scouting Group provided the cruiser screen for the task force. On 24 September, Karlsruhe departed Kiel, bound for Libau, where she arrived the following day. On 26 September, she helped carry infantry units to Putziger Wiek, where the men were loaded onto the capital ships of the invasion fleet. Karlsruhe thereafter returned to Libau on 2 October, where she embarked two officers and seventy-eight enlisted men from the Saxon Radfahr-Bataillonen (Bicycle Battalion). The ship then left Libau on 11 October as the leader of the 2nd Transport Group.[8][9]

The operation began on the morning of 12 October, when Moltke and the III Squadron ships engaged Russian positions in Tagga Bay while the IV Squadron shelled Russian gun batteries on the Sworbe Peninsula on Ösel.[10] The men aboard Karlsruhe went ashore in Tagga Bay that morning; she left the area in company with ten transport ships on 17 October and escorted them back to Libau.[9] Over the course of the next two days, Karlsruhe and the rest of II Scouting Group covered minesweepers operating off the island of Dagö, but due to an insufficient number of minesweepers and bad weather, the operation was postponed.[11] By 20 October, the islands were under German control and the Russian naval forces had either been destroyed or forced to withdraw. The Admiralstab then ordered the naval component to return to the North Sea.[12] Karlsruhe returned to Kiel before proceeding to the North Sea on 27 October, where she resumed coastal defense duties. From 16 November to 6 December, she underwent periodic maintenance.[9]

Later career

[edit]In early April 1918, Karlsruhe supported the laying of a defensive minefield in the North Sea that was laid in preparation for a major fleet operation later that month. She then took part in the abortive fleet operation on 23–24 April to attack British convoys to Norway. I Scouting Group and II Scouting Group, along with the Second Torpedo-Boat Flotilla were to attack a heavily guarded British convoy to Norway, with the rest of the High Seas Fleet steaming in support. During the operation, Karlsruhe and Graudenz were the leading vessels in the German formation. While steaming off the Utsira Lighthouse in southern Norway, Moltke had a serious accident with her machinery, which led Scheer to break off the operation and return to port by 25 April.[9][13] From 10 to 13 May, Karlsruhe and the rest of II Scouting Group escorted the minelayer Senta while the latter vessel laid a defensive minefield to block British submarines form operating in the German Bight. Later that month, she escorted the new dreadnought battleship Baden. II Scouting Group thereafter conducted additional training in the Baltic from 11 to 12 July. Karlsruhe's commander served as the commander of the group while the group commander, Kapitän zur See (KzS—Captain at Sea) Magnus von Levetzow, was away for the meetings that led to the formation of the Seekriegsleitung (SKL—Maritime Warfare Command). Levetzow returned on 5 August, Karlsruhe having gone into the shipyard for maintenance on 1 August.[14]

Karlsruhe took part in evacuation efforts on the coast of Flanders on 14 August in the aftermath of the Battle of Amiens. She loaded seventy mines, with the intention of laying a minefield in company with the cruisers Brummer and Nürnberg, but the operation was cancelled when it became clear that Nürnberg had to be drydocked for repairs. Karlsruhe took part in training operations in the Baltic from 16 to 23 October, after which she resumed guard duties in the German Bight.[9] Later that month, Karlsruhe and the rest of the II Scouting Group were to lead a final attack on the British navy. Karlsruhe, Nürnberg, and Graudenz were to bombard targets in Flanders while Pillau, Cöln, Dresden, and Königsberg were to attack merchant shipping in the Thames estuary, to draw out the British Grand Fleet.[15] Admirals Reinhard Scheer and Franz von Hipper intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to secure a better bargaining position for Germany, whatever the cost to the fleet. On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on Thüringen and then on several other battleships mutinied. The unrest ultimately forced Hipper and Scheer to cancel the operation.[16]

Internment and scuttling

[edit]

Following the capitulation of Germany in November 1918, most of the High Seas Fleet's ships, under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, were interned in the British naval base in Scapa Flow.[17] Karlsruhe was among the ships interned, and the II Scouting Group commander, KzS Victor Harder, came aboard Karlsruhe for the voyage to internment since his normal flagship, Königsberg, was not included on the list of ships to be interned.[2] The German ships, which had been escorted across the North Sea by the Grand Fleet, stopped initially in the Firth of Forth on 21 November, where over the following days, they were moved to Scapa Flow in smaller groups. Karlsruhe and several other vessels sailed north to Scapa on 26 November, arriving the following day. Over the following weeks, many men from the German ships were sent home, leaving skeleton crews to maintain the ships through internment.[18]

The fleet remained in captivity during the negotiations that ultimately produced the Versailles Treaty. Von Reuter believed that the British intended to seize the German ships on 21 June 1919, which was the deadline for Germany to have signed the peace treaty. Unaware that the deadline had been extended to the 23rd, Reuter ordered the ships to be sunk at the next opportunity. On the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training maneuvers, and at 11:20 Reuter transmitted the order to his ships;[19] Karlsruhe sank at 15:50, one of the last ships of the fleet to sink. She was never raised for scrapping, as she had sunk in a greater depth than many of the other ships.[2][9] The rights to her wreck were sold to Metal Industries in 1955, and over the following years the rights were re-sold to a number of other firms. During this period, valuable components of the ship were removed using explosives.[20]

In 2017, marine archaeologists from the Orkney Research Center for Archaeology conducted extensive surveys of Karlsruhe and nine other wrecks in the area, including six other German and three British warships. The archaeologists mapped the wrecks with sonar and examined them with remotely operated underwater vehicles as part of an effort to determine how the wrecks are deteriorating.[21] The wreck at some point came into the ownership of the firm Scapa Flow Salvage, which sold the rights to the vessel to Tommy Clark, a diving contractor, in 1981. Clark listed the wreck for sale on eBay with a "buy-it-now" price of £60,000, with the auction lasting until 28 June 2019.[22] The wreck of Karlsruhe ultimately sold for £8,500 to a private buyer, while the three dreadnoughts Clark had also placed for sale were purchased by a company from the Middle East for £25,500 apiece.[23] Her wreck lies at 25 m (82 ft) and remains a popular site for recreational scuba divers.[24]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Dodson & Nottelmann, p. 155.

- ^ a b c d e f Gröner, p. 113.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 162.

- ^ Dodson & Nottelmann, p. 156.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 86.

- ^ Staff, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 213–215.

- ^ Barrett, p. 127.

- ^ a b c d e f Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 87.

- ^ Halpern, p. 215.

- ^ Barrett, p. 218.

- ^ Halpern, p. 219.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 418–419.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 87, 147–148.

- ^ Woodward, p. 116.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 280–282.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 282.

- ^ Dodson & Cant, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Herwig, p. 256.

- ^ Dodson & Cant, p. 54.

- ^ Gannon.

- ^ "Scapa Flow: Sunken WW1 battleships up for sale on eBay". BBC News. 19 June 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Sunken WW1 Scapa Flow warships sold for £85,000 on eBay". BBC News. 9 July 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ "SMS Karlsruhe Wreck Intro". Retrieved 23 October 2020.

References

[edit]- Barrett, Michael B. (2008). Operation Albion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34969-9.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4198-1.

- Dodson, Aidan; Nottelmann, Dirk (2021). The Kaiser's Cruisers 1871–1918. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.

- Gannon, Megan (4 August 2017). "Archaeologists Map Famed Shipwrecks and War Graves in Scotland". Livescience.com. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 2. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ASIN B003VHSRKE.

- Staff, Gary (2008). Battle for the Baltic Islands. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84415-787-7.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

- Woodward, David (1973). The Collapse of Power: Mutiny in the High Seas Fleet. London: Arthur Barker Ltd. ISBN 978-0-213-16431-7.